“High-protein” is the biggest buzzword in nutrition, having dethroned predecessors “low-fat” and “low-sugar” as the food industry’s compound adjective of the moment. Historically the domain of lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs, beans, lentils, nuts, seeds, tofu and dairy products, you can now find products ranging from bottled water to breakfast cereals to Pop-Tarts fortified with it and generally trumpeting protein’s presence on the packaging.

As so many shaker bottles attest, protein supplements are also in vogue — in particular, the protein powders that those shaker bottles help dissolve into liquid. Which begs some questions: How much protein do we actually need? Are protein supplements a good way to up protein intake? Will too much protein cause weight gain? Are protein supplements safe?

UCHealth Today gathered expert insights from dietitians and a toxicologist to answer these questions and more.

What is protein, actually?

We tend to talk about protein in the singular “protein,” but it’s really about “proteins.” There are thousands of different proteins in and about our cells. Each is a long chain of some combination of the 22 amino acids that comprise all proteins in the body. Those chains then fold back on and around themselves in countless ways. Every cell in your body is partially made of protein, and all cells make use of it in various ways.

What roles do proteins play in the body?

Protein is best known for building muscle, and that’s the key driver of the protein-supplements business. But muscle and tissue development, maintenance and repair are among the many important roles proteins play in the body. Enzymes, which enable or speed up biochemical reactions, are proteins. Many hormones — chemical messengers between organs — are proteins, as are energy and nutrient transporters such as hemoglobin, which carries oxygen from lungs to cells throughout the body.

The keratin in your hair and fingernails, the collagen in your bones, tendons and skin, and the elastin that lets your arteries and lungs expand and contract are proteins. The antibodies your immune system depends on are proteins, and proteins also are critical in maintaining proper blood pH (acid-base balance) as well as fluid balance. Finally, protein can serve as an energy source, though the body much prefers to metabolize sugars and fats.

“There are so many things that protein steps up to do that other macronutrients cannot do,” said Cathy Deimeke, a UCHealth registered dietitian and diabetes educator.

New federal dietary guidelines now recommend more daily protein. On Jan. 7, 2026, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services released updated dietary guidelines that call for higher protein intake and encourage people to avoid ultra-processed foods and added sugars. These changes have prompted many questions about how much protein we need and whether supplements help.

How much protein do I need?

That depends on how big you are, how active you are, what activities you’re doing and how old you are.

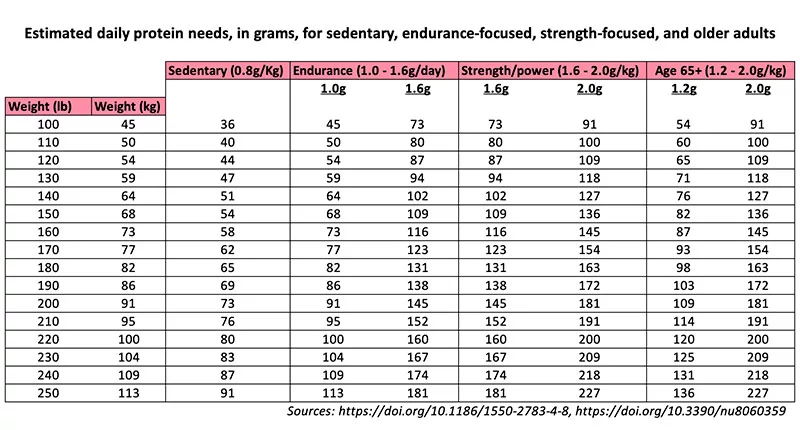

The rule of thumb for sedentary adults is 0.8 grams of daily protein intake per kilogram of body weight (0.45 grams of protein per pound). For a 150-pound adult, that’s about 54 grams of protein a day. For a 120-pound adult, it’s 44 grams.

“That’s the starting point, but for most people, I go a little higher,” Deimeke said.

But as the chart below shows, estimated protein needs really do depend on the person. Athletes require more protein to recover and build muscle: 1-1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight per day for endurance athletes and 1.6-2 grams per kilogram of body weight per day for those doing strength- and power-focused training, according to the International Society of Sports Nutrition.

Those over 65, who increasingly deal with the inevitable age-related muscle loss (sarcopenia), also need more protein — roughly as much as a younger person doing routine strength- or power-focused training. Based on that, an older 150-pounder’s ideal protein consumption would be 82 to 136 grams per day.

Daily protein needs based on weight, activity level and age

Do runners, bikers, fitness buffs and other active people need to supplement proteins?

Assuming a balanced diet, the vast majority of us, including the very active, get enough protein through what they eat, Deimeke said. Her general rule of thumb is that 20% of calories should arrive through protein. Because people who burn more calories and tax their muscles through physical activity will naturally be hungrier, they will generally consume more protein as a matter of course, she said. In essence, increased appetite leads to higher protein intake.

Also, high-protein foods can cover even elevated protein needs without undue focus on the macronutrient. Four ounces of chicken breast, a serving about the size of the palm of your hand, has 30 grams of protein, and the same amount of beef has only slightly less. A cup of cottage cheese has 25 grams, a can of tuna or a cup of Greek yogurt 20 grams each. Nuts, lentils, tofu and other foods add to the tally.

But again, there’s no one answer to how much protein people need or how to deliver it, Deimeke said.

“We’re going to take a look at underlying health conditions. We’re going to look at the level of activity. So, it’s just not one-size-fits-all,” she said.

Do I need protein supplements at all?

Most of us don’t, Deimeke said. But protein supplements can help in a couple of ways. The 20 to 30 grams of protein in a protein supplement can help quell post-workout hunger, and in a quantity that the body can readily metabolize (roughly 0.4 grams per kilogram of body weight every couple of hours, or 27 grams for our 150-pounder). Also, for people who are generally food averse or the aged whose declining appetites can’t keep up with increasing protein needs, protein bars and shakes can be a quick, efficient way to catch up.

Explore expert UCHealth Today articles on other supplements, including vitamins and minerals for better health:

“That’s where protein drinks and supplements are very nice, because they’re an efficient way for people to take in calories and protein, especially when they don’t feel like eating,” Deimeke said.

What if I eat too much protein?

Like carbohydrates, protein contains about four calories per gram (fat holds nine calories per gram). Unlike carbohydrates and fat, the body doesn’t store protein for future use. If we don’t get enough dietary protein, our body breaks down structural proteins. It also can convert amino acids to glucose for immediate energy. It’s important to note, Deimeke said, that taking in adequate carbohydrates and fat protects amino acids from being used for energy, thus allowing protein to accomplish its many roles. Taking in too much protein when carbohydrate intake is adequate will result in amino acids being converted to fat, she said.

Taking in more protein than the body needs is, thanks to that conversion, generally safe for healthy people. Because processing that extra protein makes the kidneys work a little harder, those with kidney problems who are thinking about boosting their protein intake should consider reaching out to a dietitian to establish a baseline, Deimeke said.

Consumer Reports found lead in protein powders — should you be worried?

Dr. Kennon Heard, section chief of Medical Toxicology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a UCHealth Emergency Medicine physician, said there’s no “safe” level for lead consumption. But, he said, the levels of lead that Consumer Reports testing found would result in much less exposure than people routinely experienced in the 1950s and 1960s, when leaded gasoline and lead-soldered food cans were prevalent.

“The bottom line is, yes, there’s no good effect from having lead in your body. That said, the primary problem that we see is usually in children, and it has more to do with development,” Heard said. “In adults, there’s less evidence that lead causes problems until you get pretty high concentrations, and then there’s some strong evidence that it can cause problems with blood pressure and kidney problems.”

Robin Bingham, director of nutrition therapy for UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital and UCHealth Longs Peak Hospital, notes that the Consumer Reports “levels of concern” were based on California’s Proposition 65 maximum allowable dose level of 0.5 micrograms per day per deciliter of blood. That’s much lower than the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s interim reference level of 8.8 micrograms per day for women of childbearing age (designed to limit exposure during pregnancy) or even the 2.2 micrograms per day for children.

In an email, Bingham also said that there are studies that “have not found an increased risk of non-carcinogenic health effects due to heavy metal exposure from protein powder.” Environmental exposures appear to far outweigh any contribution from lead in protein supplements. Meaning: Be aware of lead content in protein powders, but don’t necessarily be wary of it.